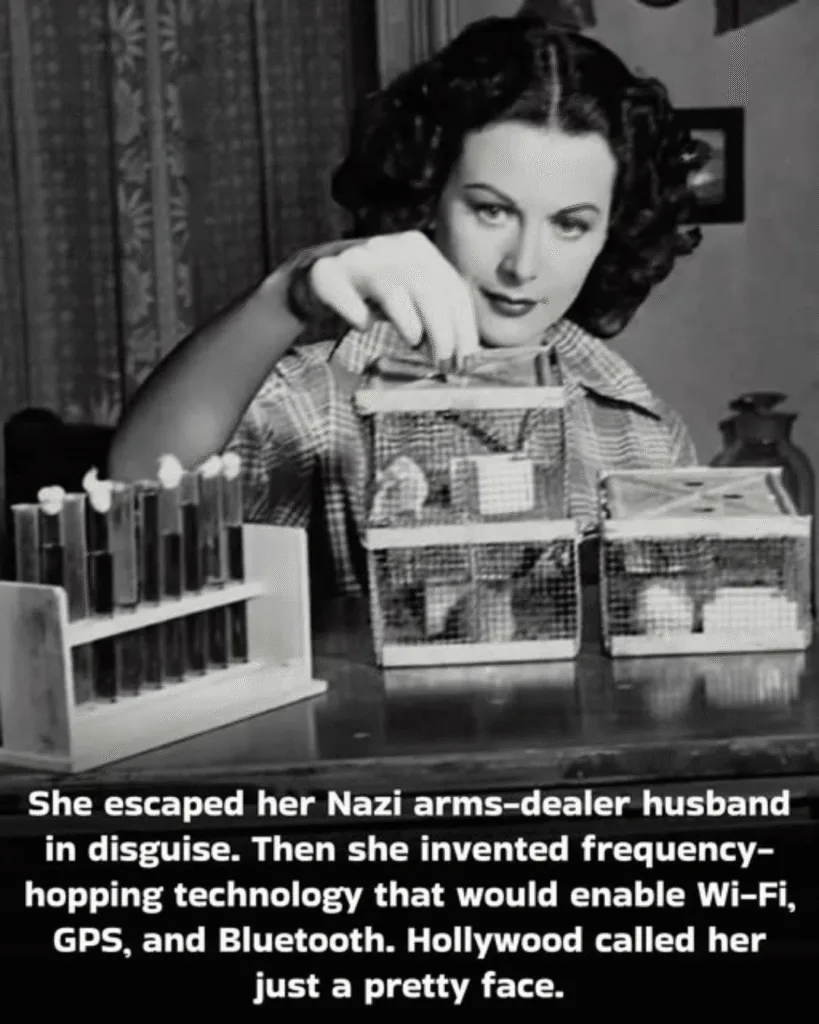

Hedy Lamarr: Hollywood Star, Spy, and Unsung Genius

Hedy Lamarr’s life reads like a thriller: a young woman born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna who fled an oppressive, well-connected husband, reinvented herself in Hollywood, and quietly engineered ideas that later powered the wireless world. The public saw glamour and screen charisma. Behind closed doors she tinkered with inventions that were decades ahead of their time.

Early curiosity and a daring escape

Raised in a household where science and the arts coexisted, Hedwig absorbed mechanical ideas and technical thinking early on. Her marriage as a teenager to an older man involved with influential figures in Europe curtailed her freedom. Risking arrest and public scandal, she escaped in disguise and sailed to the United States, changing her name and image to become Hedy Lamarr, a leading Hollywood actress.

From movie sets to mechanics

In Hollywood she dazzled audiences, but Lamarr never stopped asking how things worked. She converted curiosity into practical experimentation: building radio-controlled devices for fun, sketching ideas in notebooks, and studying engineering texts. Her tinkering wasn’t a hobbyist’s pastime—it was the seed of a technological breakthrough.

The invention: frequency hopping and how it worked

During World War II, Lamarr became alarmed by the ease with which radio signals could be jammed, putting Allied ships and submarines at risk. Teaming with composer and inventor George Antheil, she co-developed a system called frequency hopping. Instead of broadcasting on a single frequency, the transmitter and receiver would switch rapidly among many frequencies in a synchronized pattern.

This hopping made it nearly impossible for an enemy to jam or intercept the transmission unless they knew the exact sequence. The mechanism used a method similar to a musical player piano roll to synchronize changes—an ingenious cross-disciplinary approach that blended Lamarr’s curiosity with Antheil’s mechanical background.

Patent, rejection, and eventual recognition

Lamarr and Antheil received a U.S. patent in 1942. The Navy initially dismissed the idea, partly because it came from a film star and because the technology to implement synchronized frequency-hopping at scale was immature. For decades the patent gathered dust, while Lamarr continued her acting career and private inventing.

- 1942: U.S. patent granted for a ‘Secret Communication System.’

- 1950s–1970s: Technology catches up as electronics miniaturize.

- 1990s–2000s: Core ideas become foundational for spread-spectrum communication.

Legacy: Wi‑Fi, Bluetooth, GPS, and beyond

When electronics advanced and spread-spectrum techniques became practical, the ideas behind frequency hopping were adopted across many fields. Modern wireless standards—Wi‑Fi, Bluetooth, and parts of GPS—use principles related to spread-spectrum communications and secure frequency management. Lamarr’s patent is now widely recognized as an early conceptual building block for these technologies.

Genius often hides where we least expect it: a Hollywood star who changed the way the world talks.

Overlooked because of beauty and gender

For much of her life, Lamarr was typecast by the public and the press as a glamorous image, while her technical contributions were ignored or trivialized. This dismissal reflected cultural biases of the time: beautiful women were expected to be ornamental rather than intellectual. Only late in life did Lamarr receive broader recognition, including awards, honorary degrees, and public acclaim for her inventive mind.

Practical takeaways from Hedy Lamarr’s story

- Curiosity transcends roles: creative careers and scientific thinking can coexist.

- Cross-disciplinary collaboration can yield unexpected breakthroughs.

- Recognition may be delayed, but fundamental ideas can outlast initial dismissal.

Conclusion: a life that reshaped the wireless world

Hedy Lamarr’s story is more than a Hollywood biography. It’s a reminder that innovation can come from unexpected places, and that social perception often lags behind technical merit. Her daring escape from danger, reinvention on the silver screen, and quiet work on frequency hopping left a tangible imprint on modern life. Every time we connect to Wi‑Fi, pair a Bluetooth device, or rely on secure wireless links, we’re using descendants of ideas she helped pioneer—proof that brilliance can be as transformative as it is surprising.