Introduction

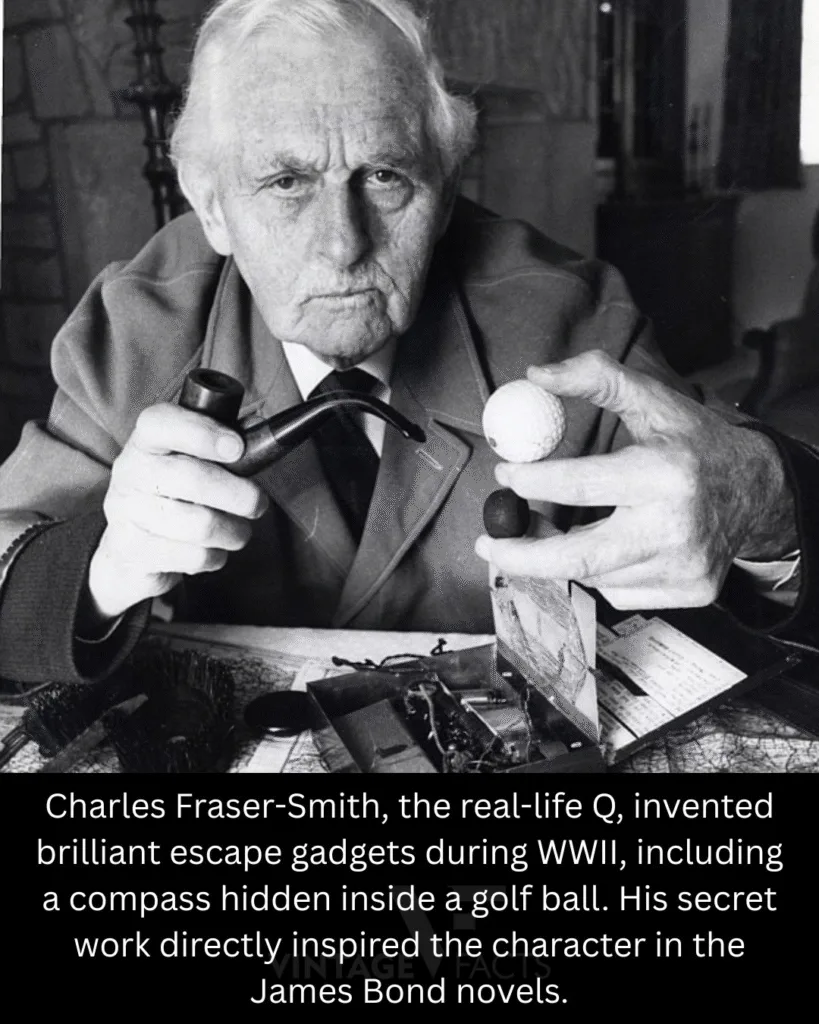

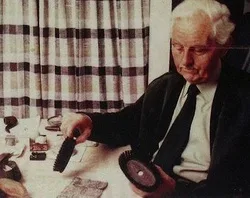

During World War II, a quiet but brilliant effort took place behind the ordinary doors of the British Ministry of Supply. Charles Fraser-Smith led a small, secretive department dedicated to designing ingenious tools of escape and evasion for Allied prisoners of war and covert operatives. Unlike the sensationalized arsenal of fictional spycraft, Fraser-Smith’s creations were purposely unflashy: they were small, concealed, and engineered to save lives rather than to harm.

Purpose and philosophy

Fraser-Smith’s unit focused on non-lethal ingenuity. The brief was straightforward: help men get home. Devices were meant to be overlooked by guards, concealed within everyday objects, and reliable under pressure. This approach prioritized subtlety and survivability over spectacle—design principles that made the gadgets effective in real-world escape attempts.

Notable inventions

A few of Fraser-Smith’s solutions became legendary in hindsight because they show the cleverness and practicality of his work. Common techniques included embedding useful tools inside objects that would never be suspected of containing contraband.

- Miniature compasses secretly embedded in golf balls, allowing escapees to maintain a sense of direction while traveling on foot.

- Flexible saw blades woven into bootlaces so prisoners could quietly cut through bars or wire.

- Maps and microphotographs hidden in the spine of books or inside false-bottom tins for smuggling information past inspections.

- Disguised currency, forged documents, and specially treated clothing to help prisoners blend in with civilian populations during escape attempts.

- Compact survival kits hidden in everyday items such as toiletries, pens, and sewing kits so evacuees could carry essentials without suspicion.

Techniques that mattered

Designers emphasized materials, concealment, and ease of use. Tools had to survive rough handling, avoid detection by casual searches, and be operable by men under extreme stress. Innovations included low-profile mechanisms, corrosion-resistant steels, and adhesives and seams that could be resealed after use. The art was often in the hiding place rather than the tool itself.

His inventions were designed not to maim, but to help men return to safety, often hidden inside the mundane.

Secrecy and service

Many of Fraser-Smith’s projects were classified for decades, meaning the men he helped rarely knew the origin of the lifesaving objects they used. The secrecy ensured both operational security and the safety of collaborators. As a result, his contributions remained largely unrecognized by the public for years, even though they probably saved many lives.

Influence on popular culture

Ian Fleming, who worked in naval intelligence during the war, was aware of the kind of ingenuity Fraser-Smith represented. Fleming adopted the idea of a specialized workshop that supplied agents with clever, concealed devices and made it central to his James Bond novels in the form of Q Branch. Where Fleming’s Q produced dramatic, weaponized gadgets for fiction, the wartime prototypes were overwhelmingly concerned with escape, survival, and subtlety.

Legacy: from secrecy to symbol

Over time, the reality of Fraser-Smith’s work and the fictionalized Q Branch influenced one another. The Bond films helped popularize the notion of a gadget laboratory, and the films in turn shaped public expectations of intelligence technology. The irony is that modern British intelligence now has an official head of technology popularly referred to as Q, a nickname that acknowledges the cultural loop between wartime ingenuity, Fleming’s fiction, and cinematic invention.

Why it still matters

The story of Charles Fraser-Smith reminds us that the most consequential innovations are not always the loudest or the most dramatic. In wartime and peacetime alike, design that focuses on human survival, discretion, and utility can have outsized impact. Fraser-Smith’s restrained creativity is a lesson in prioritizing the real-world needs of people under threat.

Conclusion

Charles Fraser-Smith’s clandestine department did more than build clever curiosities; it provided practical lifelines. By hiding compasses in golf balls or saw blades in bootlaces, Fraser-Smith and his colleagues turned ordinary objects into instruments of escape. Their work remained out of the spotlight for decades, but it left a clear imprint on both history and culture. The fictive glamour of Q Branch may owe its drama to Hollywood and Fleming’s imagination, but its roots lie in the quiet, life-saving craft of men who made sure their fellows had a chance to find their way home.